The Exhibition

The following are excerpts from an interview conducted with Patrick Lundeen in May 2013.

-Pan Wendt, curator

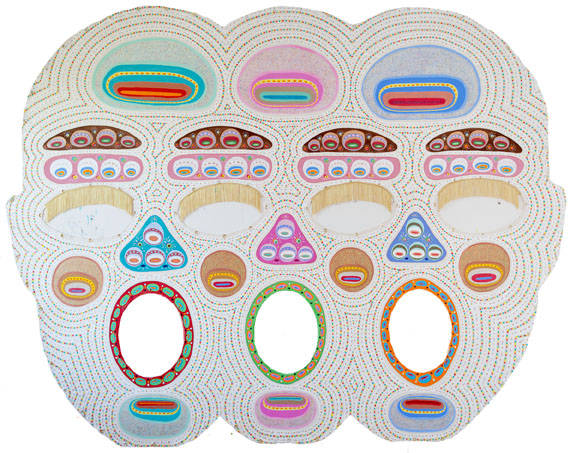

PW: To begin with, why paintings as masks?

PL: I used to work in a costume shop-which I loved! It was called Don’s Hobby Shop. It was in Calgary, downtown on Centre Street, and it was one of the coolest shops I’ve ever seen. It was really old-it had been around for more than 50 years when I worked there-and had started out as a place to buy model airplanes and rockets and stuff. It had everything from glass beads-that Native Canadians used to come in and buy-to make-up, magic tricks, little plastic Nazis, rubber masks, you name it. We used to get such weird people in there-it was awesome. One of my favourite customers was this 6 foot 5 transgendered guy who used to come in and buy model tank kits. The owner (by then a really old man) didn’t have a sense of humour at all. He would tell you with a totally straight face to go downstairs and get a gross (144) of rubber chickens. I remember once they were shooting a Steven Seagal movie and they came in and bought like 10 gallons of fake blood-which we had in stock!

Anyway, I love masks and how they can transform people. Or how they become totemic for collective fears or desires. I really like folk or indigenous artwork where masks sometimes play an important role-say in Haida culture, or in Africa where the wearer of the mask becomes the thing depicted or they use the masks to scare things away. And I really love the artist Paul McCarthy who uses masks in his work. He was a big influence in art school.

PW: So masks are a way of making paintings do something different, or they draw on different cultural resources or behaviours? I see your works as a bit “too much,” or as adopting a stance towards the viewer that verges on the overly eager, even embarrassing, where the emotion or intellectual response one is supposed to have in front of a painting is short-circuited by the overpowering grin or frown of caricature and the empty black holes of openings for eyes or mouths. Does this reading resonate with you at all?

PL: I never think of my stuff this way when I am making it. It may be that I have a bit of an overbearing personality myself… I do think that when I make something I try to make it as visually dynamic as I can. You could maybe say that it is over the top in how loud and brightly coloured it is, like bright sun or music when you have a headache. I really like the paintings of Ludwig Kirchner who uses bright colours, but produces an effect that is more anxious than cheerful.

I remember one of my favourite Monty Python skits as a kid was where a couple is sitting down having a dinner date and this guy comes up and asks if he can sit down. He then keeps asking “are you sure I wouldn’t be disturbing you?” and the couple says no, with typical English reserve. Meanwhile, he keeps singing “do do dooo do” over and over again while smashing plates and stuff like that. This affected me for sure.

When I made these paintings I let them develop into characters I recognized. The painting called Uncle Eddie is sort of a caricature of an uncle of mine, married to my aunt. He was always in trouble and used to drink a lot. He was the kind of guy who used to corner you when you were a kid and start drunkenly telling you over and over again to stay in school.

PW: There’s a recurring use of “low” materials in the work, things like MAD magazine foldouts. Even the eye-mouth openings make me think of paper bag masks. This gives the works a certain vulnerability, as if you are ambivalent about the authority of the artist. And what about pop art? You are often described as a pop artist, but it seems you resist that word. How would you describe and differentiate the way you worked with found or received materials?

PL: I admit I work with a “lowbrow” aesthetic, but I never think of myself as a pop artist. Maybe I’m a bit more like John Waters, pop culture, but not exactly commodity culture, more like a loving embrace of the detritus of commodity culture. I love John Waters and I watched all his movies, I even read his books. Unlike artists like Damien Hirst or Jeff Koons, he isn’t cynical, sitting in the same hot tub with the rich people they are supposedly criticizing. The worst you could say about John Waters is that he just leaves some people with enough rope to hang themselves with.

As for the authority of the artist, I just like things to be the way they are. It took me a long time to get over trying to make everything look slick all the time. I’ve learned that slick doesn’t necessarily mean quality. Cheap things pretend to be slick. Sometimes sloppy things reveal emotion or personality- Jackson Pollock painting his stuff on the floor with house paint. When you look up close there are keys and cigarette butts in there.

PW: Once in conversation I threw out the idea that you were making shaped canvases, sort of Frank Stellas with holes poked in them, not exactly the obvious referent when it comes to giant clown-faced masks. But you really liked the connection. How come? Why does it ring true for you?

PL: I really like Frank Stella’s work a lot, especially the really dynamic and visual late work that hits you right in the stomach (and that didn’t get as much respect from critics). That is what I want my paintings to do. I use the mask format as a starting point, but really when it comes down to it, when I paint, I focus on colour, shapes, pattern, visual affect above all.

PW: I don’t want to pigeonhole you, but I feel like your work fits a generational aesthetic. Why do you think so many artists of roughly your age are constantly engaging with readymade materials that suggest a sort of regressive attitude? There seems to be a desire for the low, for creative recycling of the embarrassing side of all the objects that surround us.

PL: I think maybe we live in a time in capitalism that is similar to the time just before communism fell in the USSR. We are living it but we no longer really believe it, yet we feel powerless to change things. We know that progress is really getting us nowhere except giving us piles of garbage, and one shudders to think of where they are going. Factories in China are making literally millions of little pairs of scissors that don’t really work, destined for dollar stores, then stockings, then the trash.

And our culture is just as cheap, rehashing movies that weren’t that good to begin with because the studios have run out of new ideas and know they can make a few bucks on the nostalgia market. I mean making Texas Chainsaw Massacre with a big budget completely misses the point!

To me good art is emotional in some way (emotions can be made cheap too though!), and that is what I am striving for. I want the work to hit you at more than just a machine level.

About the Centre

About the Centre Support the Centre

Support the Centre Art Gallery

Art Gallery Arts Education

Arts Education Choral Music

Choral Music Heritage

Heritage On Stage

On Stage Live @ the Centre

Live @ the Centre